Thinking about thinking about the brain.

BY Randy MCINTOSH

A budding Randy McIntosh

When I was a budding neuroscientist in undergraduate school, I would often spend my weekends reading through edited books that were the proceedings of key workshops in the history of neuroscience. What I was most intrigued by in these books was not the chapters per se, but the transcriptions of discussions that happened after the presentations of the chapter’s author. These dialogues gave an excellent feel for the main points the author was trying to get across and the zeitgeist of the time. It really helped me to understand how people were thinking about the brain then.

This appeal for thoughtful discussion continued when I first started attending conferences. Presentations were engaging, but what attracted me was the Q&A sessions. Some could be fierce academic debates, that for the most part, were respectful but also focused on key points that supported or refuted a theory. Over the evolution of neuroscience meetings, the Q&A sessions have changed to become shorter and less about dialogue.

As a young professor I was honoured to get in invitation to the Summer Atelier, hosted by the Neuroscience Institute (NSI), which was founded by Gerald Edelman. I was invited by Giulio Tononi, whom I didn’t really know then. The NSI also was home to Olaf Sporns and, for a while, Karl Friston. You can get an idea of the intellectual firepower that was housed within the NSI. Anyway, the Summer Atelier had two goals. First, was that the person in charge was to invite people that they thought were smarter than them, which acted to facilitate discussion rather than duels. Second, was that the presenter was given 10-minutes to sketch out their ideas/theories with a felt pen and paper easel. After the presentation, the remainder of the 45-minute slot for that speaker was dedicated to working through the essence of the ideas they sketched out.

This blew me away. The format was a challenge because for those of us doing neuroimaging and computational modeling, we feel the need to show elaborate images or movies that convey our key result. Without the benefit of such audiovisual aid, I couldn’t imagine how best to get my point across.

But I did. In roughly 7 minutes, I sketched out some key ball-and-chain diagrams for functional networks in working memory, which made the point that there was no single “working memory” network, but rather that networks could reconfigure based on task demands and the internal “neural context”.

I loved this experience as both a speaker and audience member. The discussions were focused on understanding the key tenets of ideas and theories. It was uncomfortable without the audiovisual armour, but in the end the discussions provided a collective understanding that can only be gotten through honest academic debate.

Jumping ahead a few years, I was in a conversation with Susan Fitzpatrick from James S McDonnell Foundation, who had invited me to a couple of workshops focused on how neuroimaging was going to help us under human cognition. She expressed serious doubt that the current state-of-the-art in neuroimaging was going to get us anywhere unless there was a commensurate move in theories. To cut to the chase, we decided it would be a great time to set up a workshop where we would bring together eminent thinkers in theoretical and cognitive neuroscience and see if such a move toward new brain theories was possible.

I proposed to Susan that we try to use the same Summer Atelier format for this, and she loved the idea. I spent the next several months coming up with lists of smart people (there were a lot) and trying to find a venue. Some attendees would present, others were discussants . Early in the planning phase I received an email from Rolf Kotter with an invitation for a meeting he and Karl Friston were organizing on brain connectivity and the key approaches to study it anatomically, functionally, and theoretically. The first thing that I noticed was the date of the meeting was more than a year away, and second that the ideas were similar to what I had planned for my meeting, but from the perspective of an anatomist, which Rolf was. I both responded favourably to his request and also asked whether he would be interested in attending the Toronto workshop, which was now titled “What does the brain think of the mind.”

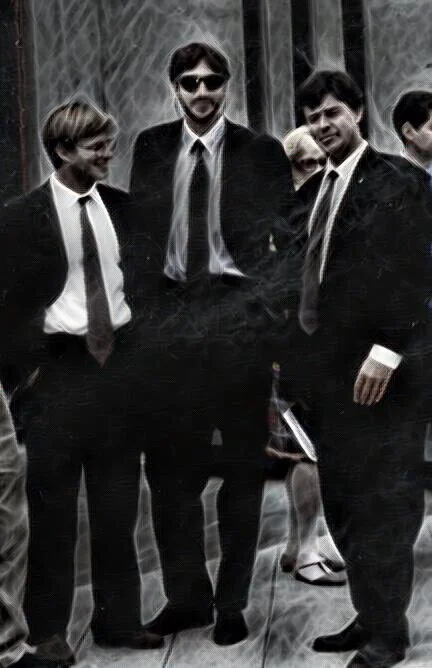

L to R: Giulio Tononi, Olaf Sporns, Karl Friston

The night before the meeting, we had a small reception where all the attendees got a chance to mingle and get to know one another. Rolf met Giulio Tononi for the first time and they started talking about theories of consciousness and organizational principles of the brain that enabled it. Giulio had just published his first book on consciousness and brought a few copies with him (at my request). Rolf was intrigued by Giulio’s ideas and got a copy of the book.

The next morning, Susan and I opened the session by giving a bit of background from the conversations that brought us to this point, and reminded the attendees of the ground rules. Ten minutes for the speaker to talk uninterrupted and then a fulsome discussion where anyone could participate.

Rolf was the first speaker. He had Giulio’s book in his hand. Rather than taking a felt pen, he placed the book on the lectern with the cover facing outwards and proceeded to talk about key principles of brain organization that made it ideal for conscious. He talked about anatomical hierarchies that could be characterized using methods from graph theory . He talked about anatomical motifs that were building blocks for functional networks by being replicated and reconfigured across the brain. He expressed the need for creation of anatomical look-up tables where one could identify the connections for a set of regions, which could then help inform the foundation for functional network. This, in retrospect, was the seed for the connectome revolution that followed about 5 years later. The amazing part of Rolf’s talk was that all these key points were made without any audio-visual aids, including sketches. Just simple, thoughtful dialogue.

Rolf’s talk set the tone for the rest of the meeting. Each speaker conveyed the essence of their idea across as succinctly as possible, and then we all spent the remaining time in a round table discussion about the idea and how it related to the link between brain and mind. It was an exhausting and incredibly rewarding meeting.

The inaugural Brain Connectivity Workshop (BCW) happened the following year. Rolf and Karl adopted the format of the Toronto meeting, with a slight adjustment: 15 minutes for the presentation with no more than 5 slides, followed by 45 minutes for discussion. Every BCW since then has followed the same format. Some speakers found clever ways to get around the 5 slide limit, but all stuck to the spirit of getting their concepts across and allowing the discussion to flow from there. In the 19 workshops that have followed, there has never been a lack of discussion and more often the moderators needed to cut it off to allow for the next presentation.

BCW has traditionally been a small meeting. With the focus on discussion that engages all participants, we’ve tried to keep the attendance to around 100, where any more can stifle the intimacy that fosters dialogue. We are in a new situation because of the pandemic. Over the past year, online scientific meetings have exploded and from my perspective have been an unintended but much needed motivation to change our meetings. Meetings are becoming more open and inclusive, and it’s time for BCW to follow suit. We’ve removed the registration cap, and are working on means to moderate the discussion so that we keep the spirit of BCW, and allow more of our community to participate.

BCW is something we desperately need in science now. We get overwhelmed by the technological wizardry and lose sight of what it is we are trying to learn. BCW gives us a chance to talk about this. I hope you find inspiration.